The Evolution of Advertising From the Bronze Plate to Display Ads

Advertising seeks to convince an individual or a group of individuals to take a certain course of action. The goal of advertising is persuasion, and for as long as humans have sought to influence each other, advertising has been around in one form or another. Present day advertising utilizes a variety of media and cutting edge technology to communicate targeted messages to audiences across the globe. From the early days of the printing press, which enabled ads to circulate widely in newspapers, to the invention of the television and Internet, advertising has evolved alongside technology, refining the ways in which advertisers can target audiences.

Advertising can be traced back to the Ancient world, where remains of ads have been found in Ancient Egypt, China, Greece, Rome and Arabia. Sales messages written in papyrus and rock wall paintings were the earliest forms of out of home (OOH) advertising, like billboards today. Ads from the ancient world, and for thousands of years thereafter, would remain highly localized.

For example, Figure 1 reflects a bronze plate ad for the Liu Family Needle Shop circa 990. Business was centered around local communities and commerce was restricted due to restrictions and difficulties with transportation.

Figure 1

With the advent of deep water navigation in the 15th Century, the most powerful empires of Europe began globalizing the world via major trade routes, which opened new markets. This, coupled at the same time with the invention of the printing press, allowed sellers to mass produce ads to be placed in newspapers that could be circulated far and wide. As the world entered the industrial revolution in the 18th Century, the capacity to produce goods and the ability to widely distribute them continued to increase dramatically.

Figure 2

In response, sellers began to “brand” their goods, or turn everyday products into household names. Early examples of this include James Lock & Co., a UK based men’s hat fitter established in 1676 and Hudson’s Bay Company, a Canadian retailer founded in 1670, see 1675 Tobacco ad in Figure 2.

A brand is defined as a product that is marketed in a uniform fashion, which ultimately establishes its own personality and image. Ranchers began “branding” their cattle two hundred years ago by burning hot iron images onto their cattle to keep track and identify ownership. With the diversity of media space available came the importance of creating a differentiated and memorable brand, from here, a new business evolved: the advertising agency. These Madison Avenue organizations would assist advertisers in creating cutting edge messaging. In today’s model, agencies focused on messaging are called creative agencies. “Creative” is the industry term for the actual content of the ad, whether that be the picture for a billboard, the 15-second audio clip for radio, the 30-second visual ad for television, or the 3”x 2” message tailored for a newspaper. These early agencies would also assist in placing the messaging in the best publications or locations.

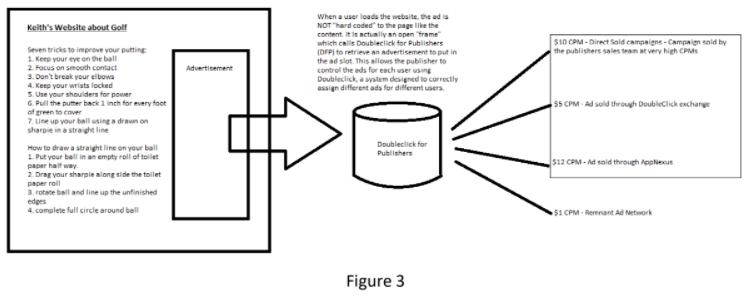

Figure 3

Advertisers within each agency would approach newspaper publishers directly to buy space on the page to promote their brands. The benefit to both parties was clear: the business would gain exposure and the publications would generate revenue. As America entered the 20th century, a variety of new media emerged to deliver ads to consumers, including radio and TV, which were present in almost every home around the country. Radio advertising began to blossom in the 1920’s followed by television advertising in the 1950’s (see Figure 3).

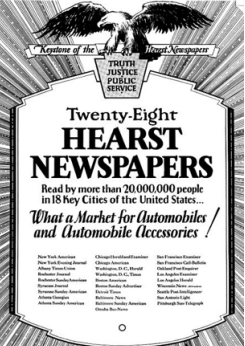

The advertising industry was growing, and with it the responsibility of placing creative in well targeted publications. The job spun off into a separate business model, creating need for a new type of company, “Media Agencies.” Once the assets or creative were produced, the Media Agency determined which medium and which publisher they should pay to show the advertisements. Media Agencies focused on aggregating advertisers in order to create leverage with pricing or buying power. By amassing a portfolio of large (high spending) advertisers, these agencies could force publishers (the biggest being the TV networks: ABC, CBS & NBC and big publishers like Hearst and Time) to lower rates across the board to win the business. While a strong portfolio dominated the early efforts by these Media Agencies, they also built strong attribution practices to determine the effectiveness of the ads placed across the landscape.

Figure 4

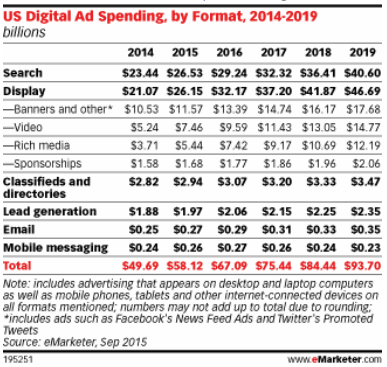

The next medium for advertising was the personal computer in

the late 1970’s and ultimately the Internet in the mid 1990’s. The ubiquity of the Internet revolutionized the ways people would come to consume content and purchase goods on a massive scale. The opportunities for advertising were (and remain) virtually unlimited, and the advertisers and media agencies would have to begin to adapt to this revolutionary, fast- growing technology. Smaller agencies focused on the new Internet technology began popping up with the aim of bridging the gap between web publishers and advertisers. These digital media agencies became indispensable, assisting advertisers in reaching this new flourishing new online audience. Advertisers began spending money on digital channels, seen in Figure 5. By the year 2000 the online industry reached $2 billion in overall media spend. Noting the chart to side overall spend will reach nearly $100 Billion by 2019.

Figure 5

These digital agencies focused their attention on the different formats available for advertising on the Internet. Google.com launched in 1996 (see Figure 6). Today they are the dominating force in Search Engine Marketing. Google allows advertisers to customize text ads, which would serve against individual Internet searches.

Figure 6

Email marketing, the next incarnation of direct mail or catalog marketing, would target individual’s email addresses with offers catered to subscriber lists. Finally, the development of the banner advertisements and visual billboards online became known as “display advertising.” The first banner advertisement, or display ad appeared on hotwired.com, the Internet publication of Wired Magazine in 1994. The ad in Figure 7, facilitated by Modem Media, was sold to AT&T.

Figure 7

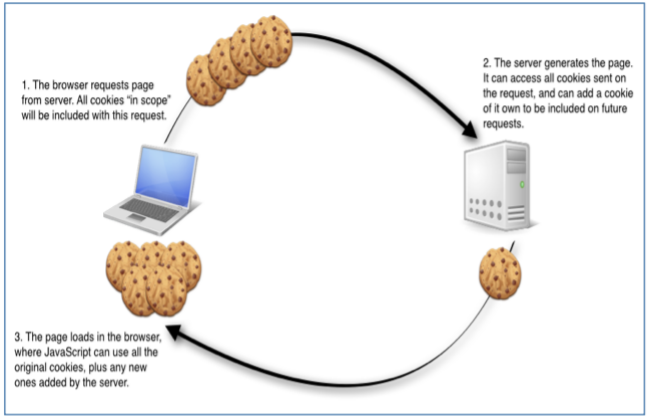

With the expansion of the World Wide Web a new market emerged. Websites, much like newspapers in the early days of advertising, began to focus on the number of people who would be exposed to the ad. With billions of web pages visited every day, the potential audience is huge, allowing advertisers to reach larger audiences than ever before. Along with unprecedented reach, display ads allow advertisers the unique ability to measure and target their audiences. As shown in Figure 8, “cookies” allow a technology provider to stamp a user’s browser with an ID number.

Figure 8

In this way, a consumer can be tracked around the Internet, much in the same way that animals can be stamped and traced. Internet technology allows direct 1:1 insight into the effectiveness of an advertising campaign. This is revolutionary compared to television, print, and OOH, which must be determined using in-store sales, loyalty cards, or unique 1-800 numbers to measure the effectiveness of an ad campaign.

With the addition of cookies, the concept of “target advertising” became a reality. It quickly became possible to serve ads on specific websites or subsets of a specific publisher. Using cookies, companies began providing profiles of how users browsed the web independent of the specific website in which the ad would appear. These capabilities, which are still evolving, provide much more control for both advertisers and publishers in how ads are placed compared to all other forms of traditional advertising. With the clear advantages of display advertising, two types of organizations emerged as suppliers of display inventory: publishers and networks. Major publishers continued to focus on the same sales strategies as they had through other channels such as a magazine. They placed ads on the top or the side of the webpage. Publishers would approach agencies to discuss specific sections (news, finance, sports, entertainment, etc.), the amount of visitation, and the demographic breakout of the audiences who regularly view these pages (as defined by third party audience verification tools). These publishers would offer this space on a CPM (cost per mille, Latin word meaning thousand) and compared the price per ad exposure or impression to the other channels, like the circulation statistics used for pricing a magazine ad.

“Ad networks” were born in the late 1990’s, first as firms whom would represent publishers and act as middlemen selling their inventory to agencies. One of the earliest networks was TeknoSurf founded in 1998, which went on to become Advertising.com and was eventually swallowed by AOL. Usually these were smaller publishers who were unable to fund their own sales teams. Boutique magazines, inspired bloggers, small newspapers, public record aggregators, and others would begin driving traffic to their websites. Networks specialized in “traffic monetization,” handling the operations behind selling and managing the banner inventory that would show on the website.

Figure 9

Ad networks came to define any organization that would amass a group of publishers and present their inventory in bulk to buyers. They could establish the same metrics as the larger publishers and sell this inventory on a CPM basis. Because their clients were usually publishers focused on producing content and not monetization, the networks could sell the inventory at a low CPM while providing the publishers with a new, and at times substantial, revenue stream.

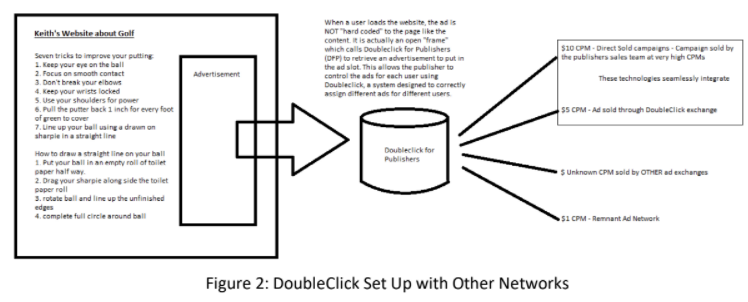

To entice advertisers, these ad networks began building in-house ad delivery technology or ad servers. This became an arms race, where the networks could customize the technology to offer new products. Founded in 1996, Double Click was one of the first third party ad servers (see Figure 10). Now it is the largest and owned by Google. They used this technology to allow advertisers to measure clicks and “conversions.” Conversions are, for example, actions taken by a user who is exposed to an ad for Nike then later buys the sneakers from Nike.com. They created frequency capping, meaning a user would only see the same ad a certain number of times per day (or per hour, month, etc.). They would sequence ads, meaning advertisers could create stories played out over several pages. These advancements in technology continued to improve drastically as computer space (servers) became cheaper and cheaper.

Figure 10

Along with the explosion of search advertising, display advertising grew year over year from 2002 through 2008. This constant growth benefited both the major publishers and the networks. According to www.adnetworkdirectory.com, there are currently 449 Networks – most of which began during the upward swing of online advertising.

The network model continues to grow today. Ad networks now come in many different forms and vary from organizations that represent very prestigious publishers on a transparent and fair basis to technology experts who use jargon to win agency budgets.

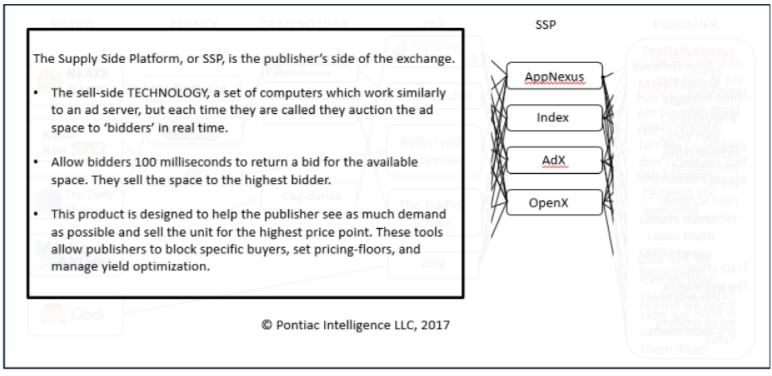

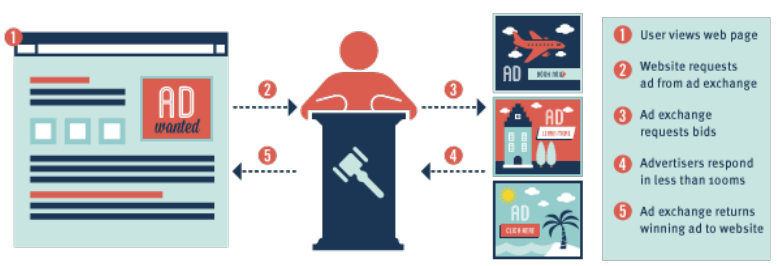

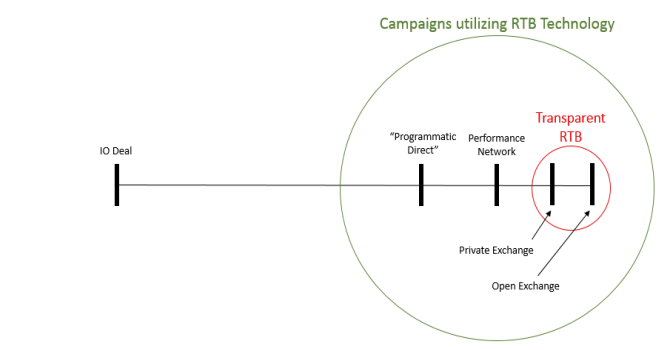

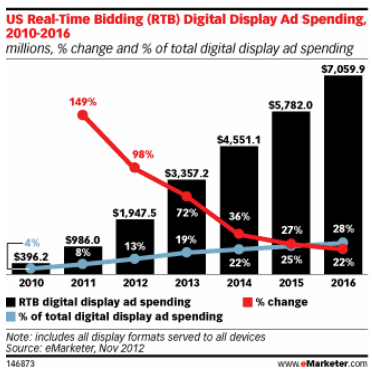

With so many different types of content providers and middle men, the world of display advertising remains very difficult to navigate. There are thousands of ad tech companies approaching agencies. Ultimately, ad serving has become a centerpiece for the entire display ecosystem. Computers became extremely cheap and extremely fast at the end of the 00s, paving the way for new developments in the Ad Tech world. In January 2007, the patent was filed for the Online Ad Exchange, which marks the official introduction of Real-Time Bidding (RTB), the next technological step in the evolution of advertising.

Download this White Paper: