Four Problems Solved by RTB

Real-time bidding (RTB) or what has become known as programmatic technology allows instantaneous decision making with regard to which ad will show on a website. Instead of deciding in advance which assets the ad server will display, now the decision can be made as the user loads the website page. The ad server runs an auction to sell the ad space in real time, forming an online ad exchange driven by a Sell Side Platform (SSP). Not surprisingly, this technology has seen strong adoption and continues to thrive today.

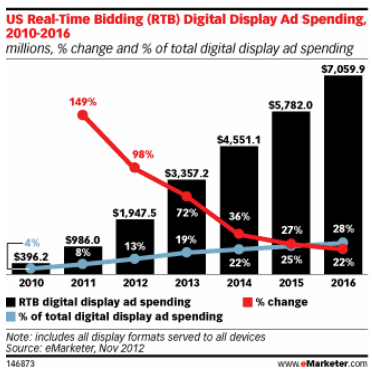

Figure 1: US RTB Digital Display Ad Spend

While the technology was developed in early 2007 it wasn’t until later that the market began adopting at scale. The technology is now used by much of the market and the amount of money spent through RTB continues to increase each yea, as seen in Figure 1. 1

RTB technology provides solutions to numerous problems that plague publishers and advertisers trying to buy and sell digital ad space. On the publisher’s side, RTB technology solves issues of forecasting and unsold inventory. On the advertiser’s side, RTB manages issues of distrust and control.

Forecasting Issues

As display advertising became a ‘must buy’ for digital agencies, all major advertisers began purchasing inventory. The most prestigious brands started cutting up-front deals with their favorite publishers. All of the leading online publishers established ‘yield management’ teams who were tasked with ensuring the rates created enough demand to fill the supply. These teams would use data from the ad server, as well as other third-party applications, to determine how many impressions were available in each section. They would then price out the inventory (available impressions) in the interest of maximizing revenue. Some publishers pulled talent from the airline industry, as they were the most advanced in supply/demand analysis and inventory management.

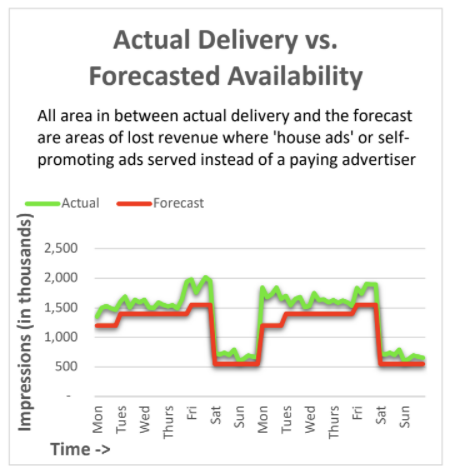

Figure 2: Actual Delivery vs Forecasted Availability Chart 1

The yield management team would use historical data to determine how many visitors on each page. Using spreadsheets, advanced database techniques, or third-party software, these teams would estimate how many ad impressions would be available for sale in the future. Sales teams would, in turn, approach the market and sell the inventory, in pieces, to any advertiser willing to

pay the premium prices. To avoid constantly providing ‘make-goods’, or future inventory due to under delivery, the yield management team would forecast 5%-10% less than the exact amount they anticipated. The inventory would vary by day and the forecasted inventory vs. sold inventory would look like the chart in Figure 2.

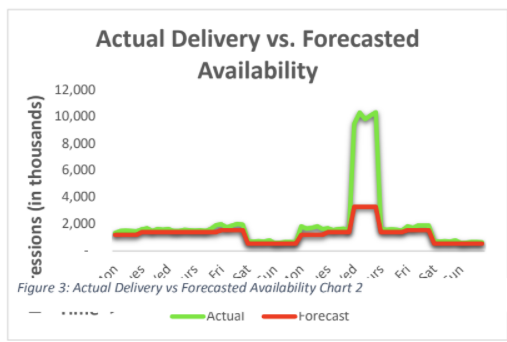

Figure 3: Actual Delivery vs Forecasted Availability Chart

Unpredictability, an inherent characteristic of the Internet, creates a far larger loss of revenue than shown above. The Internet provides the most up to the minute information possible, and when major events happen websites can see 10x the traffic they had forecasted. The supply spike can occur on a weather website as a northeaster approaches, a news website during a natural disaster, a gossip website after the sudden death of a major celebrity. The advertisers do not want ‘uneven delivery’, meaning the publisher cannot deliver all of the impressions for a 12-

week campaign in one single day. This means that when a spike of 10x occurs, even if the yield team anticipates this based on the morning numbers, they cannot deliver more than 2x or 3x the amount they predicted. The monetization of that day would look like Figure 3.

Depending on circumstance, this could equate to lost revenues anywhere from tens of thousands of dollars to several million, all due to the inability to monetize inventory in one single day.

Unsold Forecasted Inventory

Premium publishers who can sell the ability to reach a specific niche audience are often able to set their prices correctly as to sell through 100% of their inventory. Other publishers have the opposite problem. The largest internet publishers, or portals to the internet, amassed such enormous traffic they cannot sell all of their ad space at effective rates. The largest portals saw

three billion visits a day at times. Three ads on a page per day equates to 9,000,000,000 available each day. If organizations with too much inventory could determine a method to sell the long tail or ‘remnant’ inventory at even a $0.01 CPM they would make millions of dollars a month in extra revenue. While remnant solutions were available, they still could not handle the majority of this unsold inventory.

Distrust

When Ad Networks started gaining popularity circa 2000, they all represented unique publishers and could show differentiation with their ‘site lists’ or domains in which ads would serve. The biggest publishers began running their ads across several different networks. This style of yield management would become the core of the Internet publishing business. By rotating the ads, the networks began having an issue of differentiation, as the same site would be available across a variety of networks. Additionally, many of these ad networks were restricted to selling blindly or undisclosed in order not to undermine the publishers’ relationships with marketers.

To achieve the scale necessary, they began to avoid disclosing to buyers the delivery reports by domain. They would insist they could not share how the delivery varied across the websites on the ‘site list’. This would allow them to ‘dump’ a lot of inventory on a low-quality website. Facebook apps such as Farmville, websites such as myclassmates.com and dictionary.com are classic locations where you will see network ads in volumes, which are not conveyed to the agency or more importantly the advertiser. These networks could also adjust their margin

methodology and charge advertiser’s margins as high as 70%-80%.

Some networks began using other forms of technology to show differentiation. Networks claimed uniqueness by “focusing on a special audience” or “providing scale” or “using contextual search technology,” but until the advancement of the programmatic RTB exchange there was basically no difference between these organizations as they all worked with the same publishers.

As these problems leaked out of the back rooms of these networks and into the ears of media buyers, there was a clear need for greater transparency. By handling the auction for the advertising space on an impression-by-impression basis, the RTB exchange offered a technological solution.

Control

The networks were the first to implement and develop ad serving technology and continued to develop in the interest of their own bottom lines. The best advances in targeting were made available to the publishers. Publishers could use the up to date ad servers to control what type of ads would show on a certain section of a website, in a specific geographical location, or at a particular time. While advertisers could request these targeting parameters, there was no control on their side of how the ads were served. Someone on the publisher or network side needed to handle the trafficking.

As the lack of control became a growing issue on the advertiser side, the RTB technology became available. Programmatic pushed the ‘control’ into the hands of the “buy-side” or what is often referred to Demand-side. This allowed the advertiser to manage how they want to target their ads across publishers (in bulk, becoming ‘exchanges’). This was a clear benefit for all involved, as the newfound confidence led to larger budgets.

The RTB exchange provided solutions to these four issues, but the agencies we’re set in their ways and comfortable with the accustomed methods. Changing the way an entire industry behaves takes time and takes ‘buy-in’ from big players early. How could the networks and publishers ensure the advertisers would test this technology that offered ‘control’ and ‘transparency’ into pricing and targeting? They created an auction environment promising the buyers they would pay only a ‘penny’ more than the next highest bidder for each impression. This Second Price Auction method created a ‘perfect’ market allowing the next generation of media to emerge: Programmatic Media.

Download this White Paper:

References

1 http://www.iab.net/about_the_iab/recent_press_releases/press_release_archive/1996_pr_archive

2 (or nodes, or boxes, or servers – all terms which refer to a computer, usually without a monitor and in a building with no windows somewhere relatively unpopulated)

3 Pemberton, Steve. http://homepages.cwi.nl/~steven/Talks/2011/05-07-steven-visualisation/ , CWI and W3C, Amsterdam, © 2011 4 http://www.google.com/patents/US20070192356.pdf

5 http://adage.com/article/digital/real-time-bidding-account-25-display-ad-spending-2015-emarketer/238300/